UNITY 25 Under 25 Leader Dylan Baca, 18 years old, helped to make history in AZ! He created the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Initiative to push for Indigenous Peoples’ day in AZ. State Sen. Jamescita Peshlakai has been working since 2013 to get a bill passed that would replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples Day in Arizona, but she was always met with leaders telling her it would never happen.

The closest she got was in 2018, when she got a bill passed recognizing Native American Day on June 2.

“It was really a hollow victory,” she said, “June 2nd in the hottest state as a day to celebrate Native people, it was more of a slap in the face.”

Peshlakai still hasn’t passed a bill to establish Indigenous Peoples Day, but she has made some progress. On Sept. 4, Gov. Doug Ducey signed a proclamation presented by Peshlakai and the Indigenous Peoples’ Initiative that recognizes Indigenous Peoples Day on Oct. 12, which is also Columbus Day.

I’m beyond excited that Gov. Doug Ducey has signed a proclamation declaring October 12th as #IndigenousPeoplesDay in Arizona! I fully support this at the local, state, and federal level, and I’m happy to share we will also recognize Indigenous People’s Day in #Tempe this year! pic.twitter.com/OtCpUrs10B

— DoreenGarlidTempe (@DgarlidTempe) September 22, 2020

The proclamation does not replace Columbus Day as a state holiday.

“We’re grateful for the contributions and influence of Arizona’s Native American communities,” said Patrick Ptak, communications director for the Governor’s Office.

When she heard the proclamation was signed, Peshlakai said everyone involved was surprised and happy about it. She had run so many bills trying to create an Indigenous Peoples Day but was told it would never happen.

“I don’t think any other governor has ever done that,” Peshlakai said of the proclamation. “This is the first.”

Peshlakai thinks “the governor saw this as a chance to mitigate the racial tension. I really appreciate him doing this. It says a lot about where our state and our nation is hopefully headed.”

“When I introduce this legislation in January 2021, I need the momentum of this proclamation and the national movement to do this,” she added.

In the future, Peshlakai hopes to “make Columbus Day Indigenous Peoples Day and maybe make June 2 Native American Civil Rights Day.”

If her idea becomes law, she said, “it’s an opportunity to move the conversation forward and to start really working on the inclusion of Native Americans in every part of American life and opportunity.”

The proclamation says Arizona “rejects oppression against underrepresented groups that perpetuate socioeconomic disparities.” It says the state “recognizes that Indigenous people are the first inhabitants of the Americas, including lands that later become the United States of America,” and that Arizona acknowledges “historic injustices suffered by Indigenous people.”

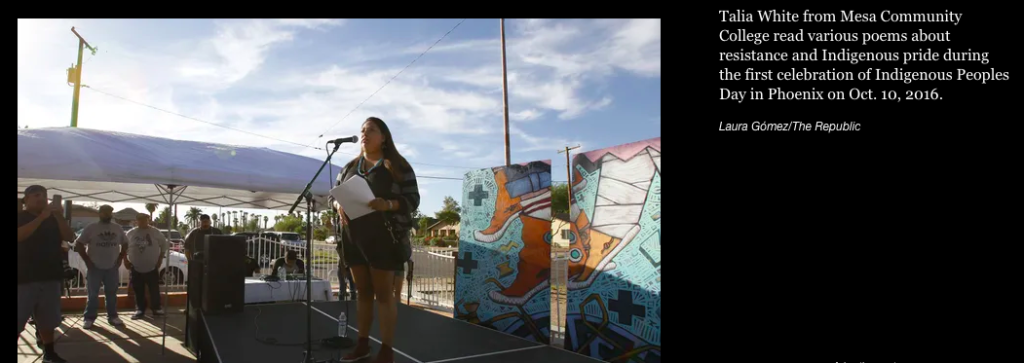

Indigenous Peoples Day has been recognized by the city of Phoenix since 2016, after the City Council voted 9-0 to establish the day as an annual city commemoration event. The city’s recognition did not create an official city holiday nor replace Columbus Day.

“I’m grateful to our Governor for signing this proclamation. This has been an effort close to the hearts of many Indigenous people,” Peshlakai, D-Cameron, said in a press release. “It is time we move beyond Columbus Day and onto a day that celebrates Indigenous people.”

Peshlakai worked with the Indigenous Peoples’ Initiative on securing the proclamation. They are also working with California Congresswoman Norma Torres to sponsor a bill recognizing Indigenous Peoples Day on the federal level.

Peshlakai praised the work of Dylan Baca, the 18-year-old president of the Indigenous Peoples’ Initiative. She said without his help the proclamation wouldn’t have been signed.

“He’s a high schooler and he’s really about inclusion. He started the nonprofit simply to pass Indigenous Peoples Day in Arizona,” she said. “This wouldn’t have happened without him. He’s the one who really lobbied the governor.

“It’s so meaningful as a political leader that we have young people like Mr. Baca that really see the value of their inputs,” she added.

Peshlakai and Baca will host an event to celebrate the proclamation at the Heard Museum on Sept. 29 at 9:30 a.m.

Baca said he’s been working with Peshlakai since January on the proclamation and he was surprised the governor signed it.

“He’s not usually one to go for something like this. But it just shows that bipartisanship is possible, especially when we try to support our marginalized communities,” said Baca, who is a citizen of the White Mountain Apache Tribe.

“Now we must work to make this a permanent holiday in Arizona. Celebrating Indigenous Peoples Day gives us an opportunity to tell a more accurate narrative of our history. This is a day to uplift our stories and communities,” he said.

The Indigenous Peoples’ Initiative, according to Baca, is a nonprofit organization that works to educate and advocate on behalf of marginalized populations to ensure that they are accurately represented.

“I started the Indigenous Peoples’ Initiative because Native Americans have been disproportionately affected more than other populations in the state of Arizona and across the nation,” he said.

Even though the city of Phoenix has recognized Indigenous Peoples Day since 2016, and Ducey signed this proclamation recognizing it in Arizona, there have been several celebrations held throughout Arizona honoring Indigenous people for years.

Indigenous Peoples Day Arizona was established in 2015, and each year the organizers host various events celebrating Indigenous communities in the state.

Indigenous Peoples Day Arizona started as a grassroots organization with the goal “to raise awareness in relation to the national Indigenous movement to abolish Columbus Day and replace with the more friendly and accurate Indigenous Peoples Day,” according to the group’s website.

“We support the efforts that our Indigenous people have been making in both the political arena as well as the organization and grassroots arena. It takes both,” said Laura Medina, an organizer with Indigenous Peoples Day Arizona.

When Medina heard about the proclamation being signed by Ducey, she said it allows “settler colonialists to acknowledge or recognize history, our culture or even us as people,” but she wonders if it is enough.