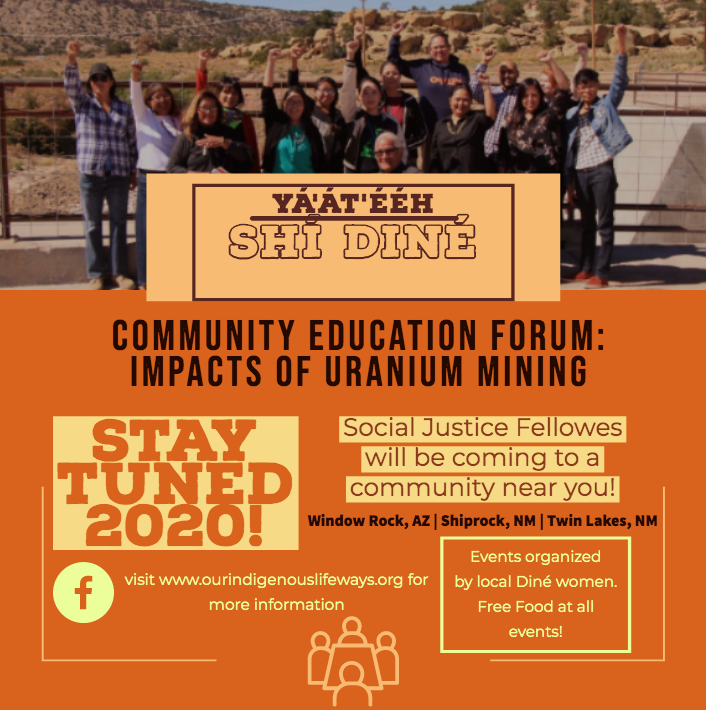

There are more than 500 abandoned uranium mines on and near the Navajo Nation, most of which have not been cleaned up, and UNITY Earth Ambassador Zunneh-bah Martin, Diné and Modoc’, New Mexico, plans to do something about this. Martin shares that she is “having a great experience with the Indigenous Lifeways Social Justice Fellowship. It is empowering to be amongst Indigenous women leaders from across the Navajo reservation and to be working on social justice issues in our communities. I believe that it is important to build these types of relationships to grow/strengthen support systems for our people who advocate for social justice. It is always comforting to know that you are not the only one who wants to make positive changes, even if you are one of a few.”

There are more than 500 abandoned uranium mines on and near the Navajo Nation, most of which have not been cleaned up, and UNITY Earth Ambassador Zunneh-bah Martin, Diné and Modoc’, New Mexico, plans to do something about this. Martin shares that she is “having a great experience with the Indigenous Lifeways Social Justice Fellowship. It is empowering to be amongst Indigenous women leaders from across the Navajo reservation and to be working on social justice issues in our communities. I believe that it is important to build these types of relationships to grow/strengthen support systems for our people who advocate for social justice. It is always comforting to know that you are not the only one who wants to make positive changes, even if you are one of a few.”

As a UNITY Earth Ambassador, Martin was nominated by a member of their community, meeting criteria that included demonstrating leadership potential, showing an interest in protecting the environment, and experience and participation in community service projects. Earth Ambassadors take their message to tribal and governmental agency representatives, as well as lawmakers and others committed to environmental stewardship.

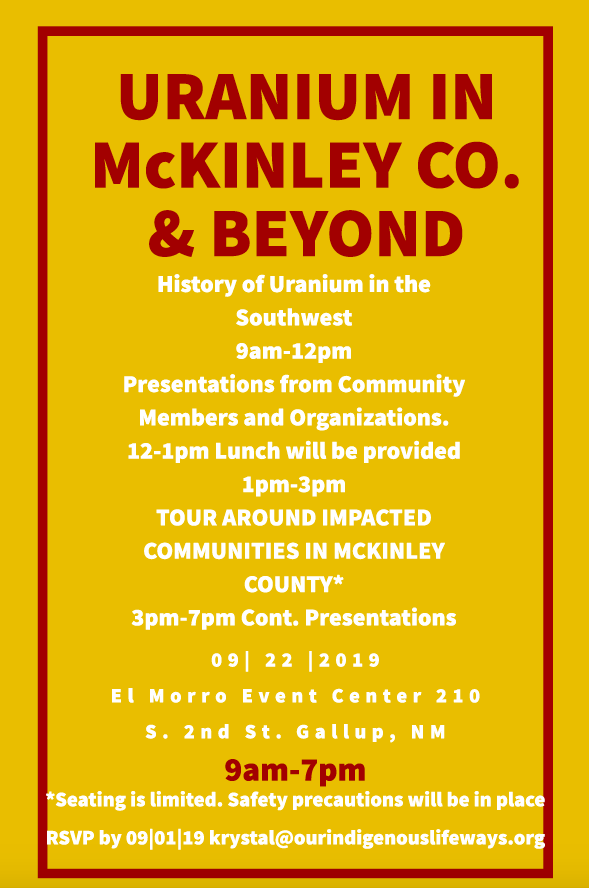

Martin further explains that “The “Uranium in McKinley County & Beyond” event had a good turnout and it was a very informative event. I am aware of the negative impacts and history of uranium mining, especially on our ancestral Navajo homelands, but I am glad that I was able to learn more details from the different presenters. I plan to continue to learn and educate about the public health and environmental health issues related to uranium. I know of many relative and community members that have been negatively impacted as well as our Mother Earth. I hope to encourage everyone to join this movement against uranium, coal, etc. mining to protect our land and people.”

“There are over 500 abandoned uranium mines on and near the Navajo Nation, most of which have not been cleaned up. We visited the Red Water Pond Road community in Church Rock, NM which is located on the Navajo Nation. This is where the largest radioactive material “accidental” spill occurred in the U.S. on July 16, 1979. Even though this spill occurred 40 years ago, it has still not been cleaned up and this toxic waste is leading to many negative health issues for our Navajo people, including diseases. We also watched the short film “Doodá Łeetso” that discusses the legacy of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation, which can be watched on the following links. Please show your support for our Indigenous relatives/land around the world and join in solidarity against environmental racism/injustice!” shared Martin.

Learn More at: Multicultural Alliance for a Safe Environment

https://swuraniumimpacts.org/red-water-pond-road-community-association/

Earth Ambassadors plan to work with the National UNITY Council Executive Committee and Representatives to campaign for environmental projects for Earth Day 2020. EAs are reaching out to elders in their communities to learn teachings about caring for indigenous resources. They plan to develop an initiative to encourage UNITY youth to approach elders and tribal leaders to carry forward traditional ways. Plans are in place to host Webinars in the near future.

UNITY hopes that the EAs will attend the 2020 Midyear and another environmental excursion. UNITY is seeking a sponsor for the 2019-2020 Earth Ambassador program. For more information contact Tami Patterson at t.patterson@unityinc.org

Martin hopes to continue to spread awareness on abandoned uranium mines through her Earth Ambassador platform.

Learn More at KOB4 News Story: Colton Shone August 19, 2019

4 Investigates: Abandoned uranium mines continue to threaten the Navajo Nation

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — There are hundreds of abandoned uranium mines scattered across the Navajo Nation.

The clean-up process has been slow for those who live right in the heart of them. For many, it’s been a decades-long fight for the removal of “hot dirt” and there’s still no real end in sight.

Red Water Pond Road Community Association is home for Edith Hood. She and her family have lived there, a few miles east of Gallup, for generations. “We had a medicine man living across the way,” she said.

It’s a remote village on Navajo land surrounded by beauty and radioactive waste. There is tons of “hot dirt” left behind from the nearby abandoned Northeast Churchrock Uranium Mine and the abandoned Kerr-Mcgee Uranium Mine Complex.

“This uranium, it’s in the air, the soil, the water, everywhere,” said Hood. She is also the community association’s president.

Teracita Keyanna also grew up here and believes the place she loves so much is killing her family.

“We suffer from respiratory illnesses, cancers, different kinds of skin ailments, there’s a lot of things that happened,” Keyanna said.

The community members have been asked by many people why they choose to live in that environment if they believe it’s toxic.

“Yes, we have heard that. I think most of us have heard that. For most of us here, we are traditionalists and in the Navajo way, you have your umbilical cord buried, you have the past ones who are buried in the hills, I said, we just don’t leave them,” Hood said.

Uranium mining was at its peak on the Navajo Nation from the 1940s to 1980s. Hood remembers her homeland bustling with miners and mill workers. Today, it’s a different story.

According to the federal Environmental Protection Agency, there are more than 500 abandoned uranium mines scattered across the Navajo Nation in New Mexico. Many are between Gallup and Grants. There are also some near Shiprock.

“We want a clean environment for our grandchildren. Will it ever happen?” said Hood.

Hood says the community didn’t even know the dirt left behind was hazardous until researchers tested it in the early 2000s.

“There was high levels, especially in the ditches. We started to band together to organize,” she said.

They held meeting after meeting with tribal, state and federal authorities to get rid of the contaminated dirt.

“I’m not comfortable talking to people in Washington or big places like that, it’s something that I told myself I need to do it because there’s nobody else who’s going to do it for us,” said Keyanna.

“I’m not comfortable talking to people in Washington or big places like that, it’s something that I told myself I need to do it because there’s nobody else who’s going to do it for us,” said Keyanna.

Attorney Eric Jantz with the New Mexico Environmental Law Center represents Red Water Pond.

“The outrage is palpable anytime there’s a meeting with EPA or interaction with the federal government. People end up very, very frustrated and angry about how they’ve been treated. Their feeling for the most part is the EPA is delaying this, delaying this until all the folks there have passed on,” said Jantz.

Jantz says they’re getting international attention by filing a complaint with the United Nations Human Rights Committee alleging minority communities, like this Navajo one, are treated unfairly in superfund site clean ups.

“In communities that are wealthier and more Anglo like for example Durango, Colorado, in the 1970s had significant tailings, uranium mill tailings in part of their community. The EPA got wind of that situation. They essentially rebuilt the entire neighborhood after they removed the tailing piles three miles off site. They did it all in a period of 7 years. So it can be done very quickly,” said Jantz.

An EPA spokesperson told KOB 4:

“We understand the community’s frustrations with delays in the cleanup. To date, EPA has removed 200,000 tons of contaminated soil. The remaining contamination at the northeast Churchrock mine is fenced off and is capped by clean soil to protect the community until the final cleanup starts.”

The EPA spokesperson says potential cleanup of the Churchrock mine is projected to start between 2021 and 2024. As for the Kerr-McGee mine, the spokesperson said it’s working on a plan comparing clean up options. That report will be released in a year.

Keyanna left the reservation and now lives in Gallup. She says she’s noticed a big difference in her family’s health now that they left. It was a tough decision to leave home, but she vows to fight for a safe environment so that one day she can return home.

“This is home and if we can get it cleaned up and we can get all these government agencies be held accountable and be here to help us move back that would be great.”