Read more in The Seattle Times (photos by Alan Berner / The Seattle Times)

Lynda V. Mapes Jim Brunner

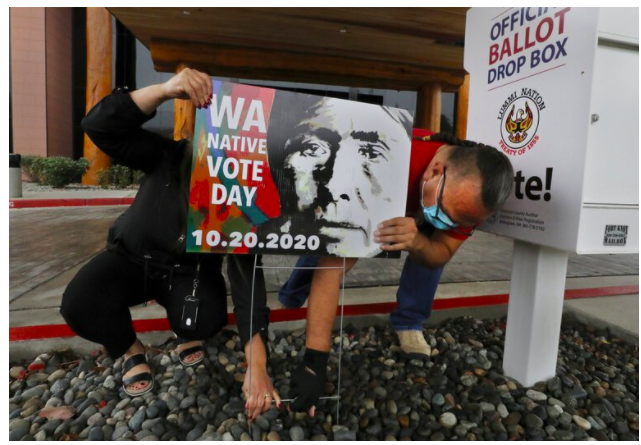

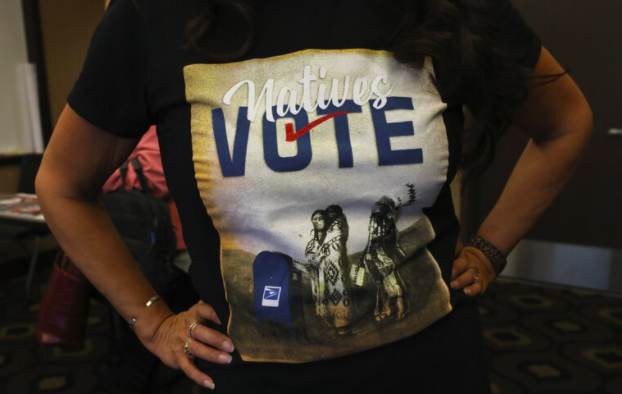

LUMMI NATION — Freddie Lane gathered up T-shirts, posters and signs at the tribal administration building, getting ready for a Native Vote 2020 rally, planned for later this month at Lummi and reservations across the state.

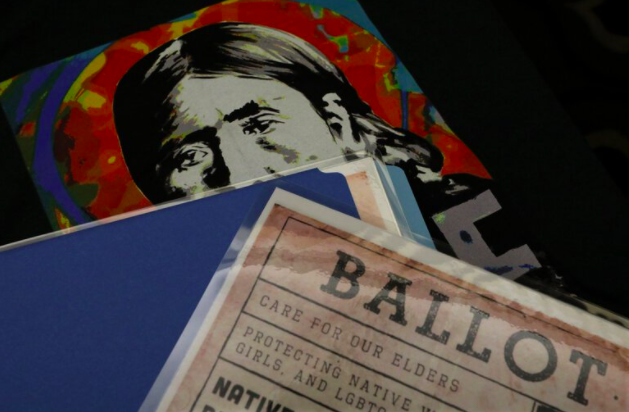

All over the get-out-the-vote swag was the image of a woman, stoic and resolute.

She is “Lummi Woman,” as the haunting photo made by Edward Curtis in 1899 is called. She was photographed in the midst of historic change after her people in 1855 signed a treaty with the United States, ceding vast swaths of their land. Yet the nation’s first people were the last to receive citizenship, under the Snyder Act passed by Congress in 1924. And it wasn’t until 1962 that every state in the nation secured the right to vote for Native people.

Today Lummi Woman’s descendants, in part to honor their ancestors and protect all that their elders reserved for them in the treaties, are rallying to get out the vote and be heard in the 2020 election.

Tribal leaders see everything at stake, from their way of life to their treaty rights, in the election between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden.

Trump has signed some bills important to Native Americans, including compensation to the Spokane people for loss of their lands in the mid-1900s, and reauthorization of funding Native language programs. And he did not block federal recognition of the Little Shell Tribe of the Chippewa Indians in Montana.

But the bigger picture is bleak from a Native perspective.

Among their concerns, Trump has downplayed the threat of a pandemic that is ravaging some tribal nations. And he has ignored the scientific evidence for climate change, even as rising sea levels are causing havoc for coastal tribes like the Hoh and as intensifying wildfires are repeatedly roasting thousands of acres of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation in Eastern Washington.

The administration’s environmental policies have been particularly offensive to tribes that rely on natural resources for their economies and cultural practices. The Trump Administration has even rolled back clean water regulations in Washington intended to protect the purity of foods that are critical to tribes, including salmon.

Every election is important. But to Native people, this election feels more like a matter of survival.

“This is for the sake of our ancestors who fought to protect us,” said Candice Wilson, former vice chair of the Lummi business council and active in the get-out-the-vote campaign. “We have the responsibility to do the same, or what will our grandchildren have? The strength of our ancestors is what makes us strong today. This is about the future.”

Tribes have already put millions of dollars of contributions into the election, according to a Times analysis of state and federal records of campaign spending. Voter registration and voter turnout also are at the heart of tribes’ election strategy.

“It’s critical,” said Lane, who last week was helping to organize the Lummi Native Vote 2020 rally, taking place Oct. 20.

Teresa Taylor, interim economic development director for the Lummi Nation, knows better than most the importance of voter turnout. She lost her reelection to the Ferndale City Council last year on a coin toss after a tie vote failed to decide the contest. “I can tell you, every vote counts,” she said, while at a planning meeting for the rally.

While they run their own governments and nations, tribes care deeply about the partners they govern with, from city councils and utility boards to school boards, judges, members of the state Legislature, and of course the governor and members of Congress and president of the United States.

That is because exercise of tribal sovereignty and even the most fundamental aspects of protecting and continuing their way of life depends on productive government-to-government relationships at every level, said Nikki Finkbonner, interim general manager for the Lummi Nation.

So much comes down to good governance with partners that honor tribal treaties and cultural imperatives, she explained, from protection of cultural resources and sacred sites, to federal funding for tribal education and housing, health care programs, and protecting natural resources and treaty rights.

“This election means so much for us right now,” said Rodney Cawston, chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation. “I don’t know how we are going to survive another four years if things don’t change.”

Tribes rally with new energy

Not since the campaign by the late GOP Sen. Slade Gorton, infamous in Indian Country for fighting treaty-protected fishing rights all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, have tribes been so energized by a federal election.

“We have 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S., and 500 who knew who Slade Gorton was,” remembered Julie Johnson, chair of the Native American Caucus for the Washington State Democrats. “All these tribes would say, ‘What are you going to do about him?’”

Plenty, it turned out. In his faceoff with challenger Maria Cantwell in 2000, tribes were regarded as the deciding edge in the tightest U.S. Senate race in Washington history.

Today, Johnson, 78, has been helping to lead a Native voter registration drive and voter turnout effort across the region. Over her lifetime she has seen a big change in Indian political activism, Johnson said, from days of apathy and even being afraid to participate in politics off the reservation.